Moving from a monolithic system to a set of services is a common architectural transition, particularly prevalent at the moment as microservices continue to gain mindshare. Like any large architectural shift, a monolith breakup is best tackled as a series of small steps that incrementally move the system towards the desired state. These incremental steps might seem less effective than making changes in large leaps, but small steps are safe. They also enable a team to evolve their system’s design while continuing to deliver features and functionality in parallel. This makes it a lot more likely that the architectural work will continue to completion.

In this blog post, I’ll describe the sequence of changes a team can use to extract a chunk of functionality out of a monolith. We’ll pick a fairly easy example to get started with — a stateless email notification service. In future posts, we’ll look at some more complex scenarios, such as extracting functionality which depends on persistent state. We’ll also see how we can use the capabilities of a feature flagging framework to make this a safe, controlled transition.

The Plan

Imagine that we’re working on a relatively large e-commerce application currently implemented as a large monolithic system. Our architectural vision is to move towards a set of fine-grained services.

We will move towards this goal slowly but surely, tackling one chunk of functionality at a time. Each chunk will be either extracted from the monolith into a new service or moved into an existing service, extending its scope of functionality.

Each of these extractions will take a while, and we want to avoid the perils of a long-lived feature branch. Instead, we will use Branch by Abstraction techniques to perform the extraction on our shared main branch using the following plan of attack:

- Choose a candidate piece of functionality within the monolith

- Gather our internal implementation of the functionality within our monolith

- Introduce an internal facade for the functionality

- Create a new externalized version of the functionality

- Create a second facade for the externalized functionality

- Introduce a Toggler which can switch between the internal and external facade

- Migrate traffic from the internal to the external

- Remove the internal functionality, remove Toggler

Choose Your Functionality

We know that the best way to slice a system into independent services is by focusing on core business capabilities. In our domain that might mean services responsible for things like Order Fulfillment and Product Catalog. This is the best way to ensure that each service is highly cohesive and that the coupling between services is loose.

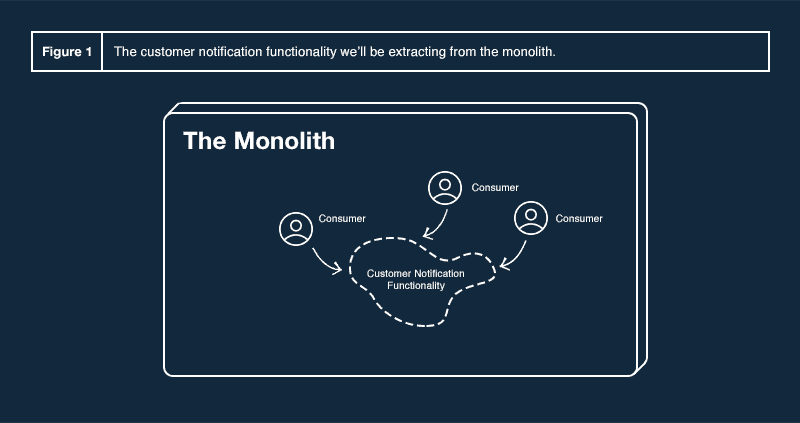

We’ve decided to start by extracting a Customer Notifications service, which will eventually be responsible for sending emails, text messages and in-app notifications to our customers to inform them of events like an order being shipping.

Gather Your Functionality

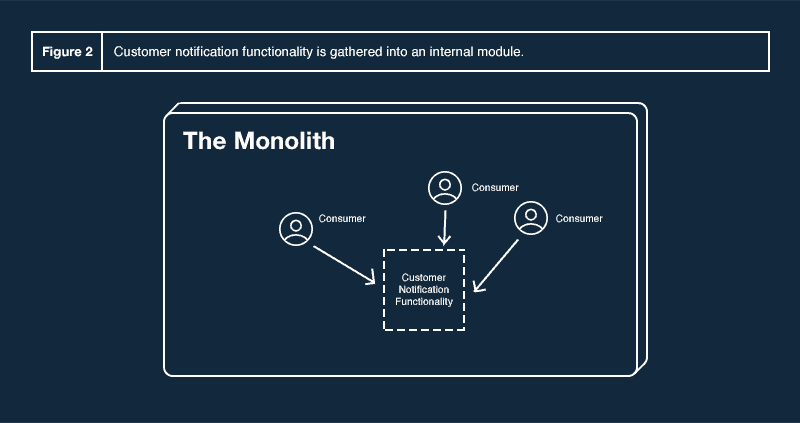

Our system is relatively mature and has been worked on by various teams over its lifetime. Different aspects of customer notification functionality are implemented in different areas of the codebase, based mostly on which team added the functionality and when it was done. We now spend some time refactoring these existing implementations to gather them into a single module without our codebase.

Introduce an Internal Facade

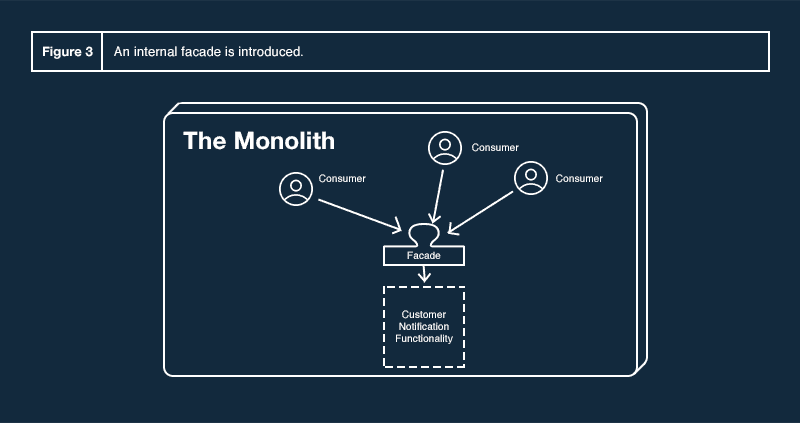

Next, we create a Facade which provides a high-level abstraction over the notification functionality and refactor all consumers of that functionality to use the facade. This provides us with a single chokepoint from which we will strangle out the functionality.

Create an Externalized Implementation

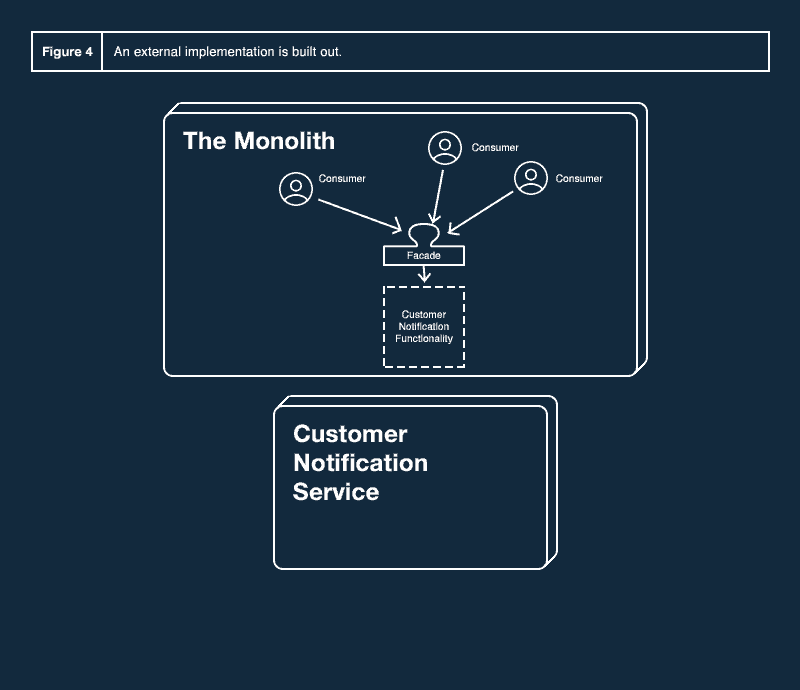

Now it’s time for us to do the fun part — create the new implementation. Sometimes it’s possible to do this by reusing the existing internal implementation, but quite often the best path is to simply re-implement the same functionality from scratch in an external service. In some cases, it will make sense to add the functionality to an existing externalized service, but in this instance, we decide to create a brand new Customer Notification service. When creating the new functionality we are careful to use the same abstractions that we used when building our facade.

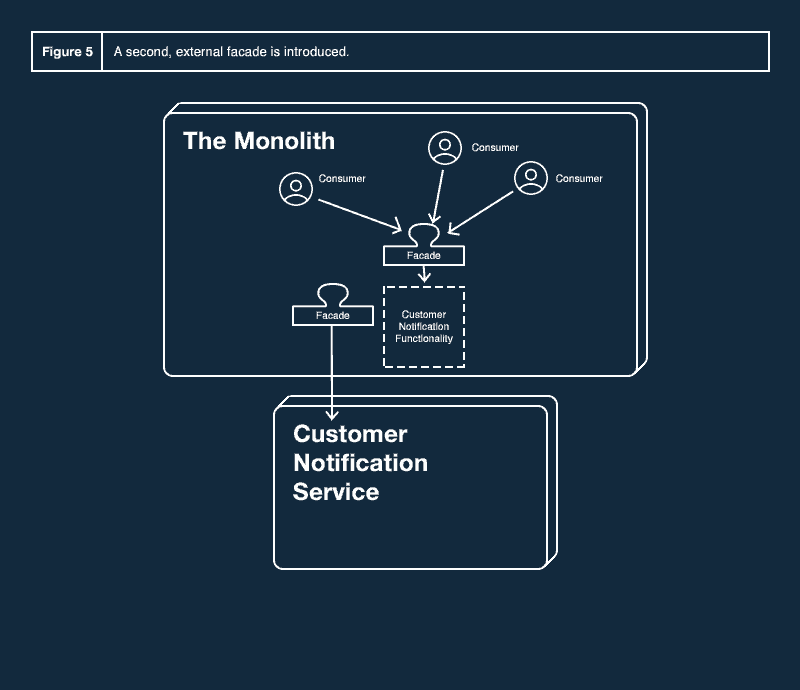

Create an External Facade

Now we add a second implementation of the customer notification facade within the monolith which simply proxies requests over to the external service.

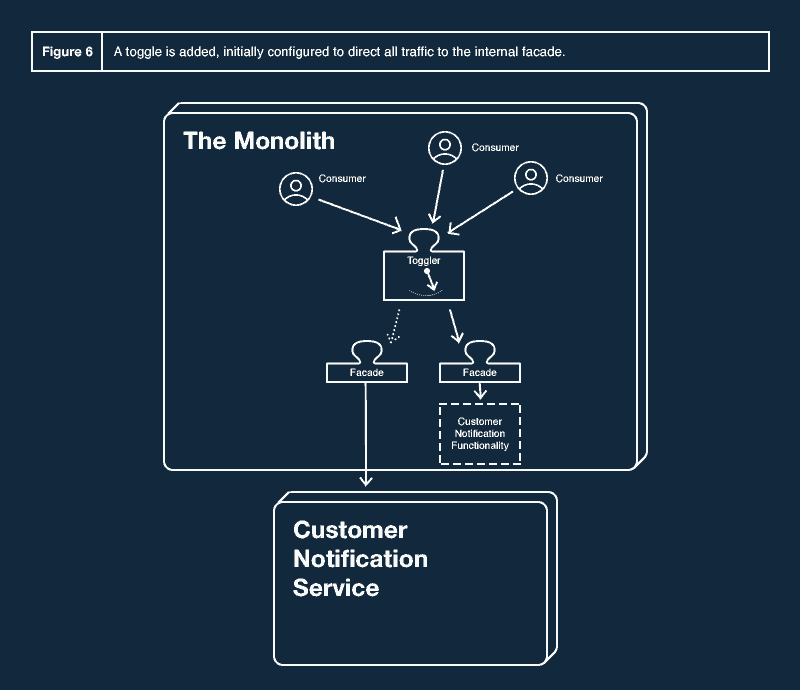

Introduce a Toggler

We now create a Toggler — a 3rd implementation of the facade which acts as a sort of traffic router, forwarding requests to either the internal facade or the external facade. This routing decision is typically configured via a feature flag of some sort.

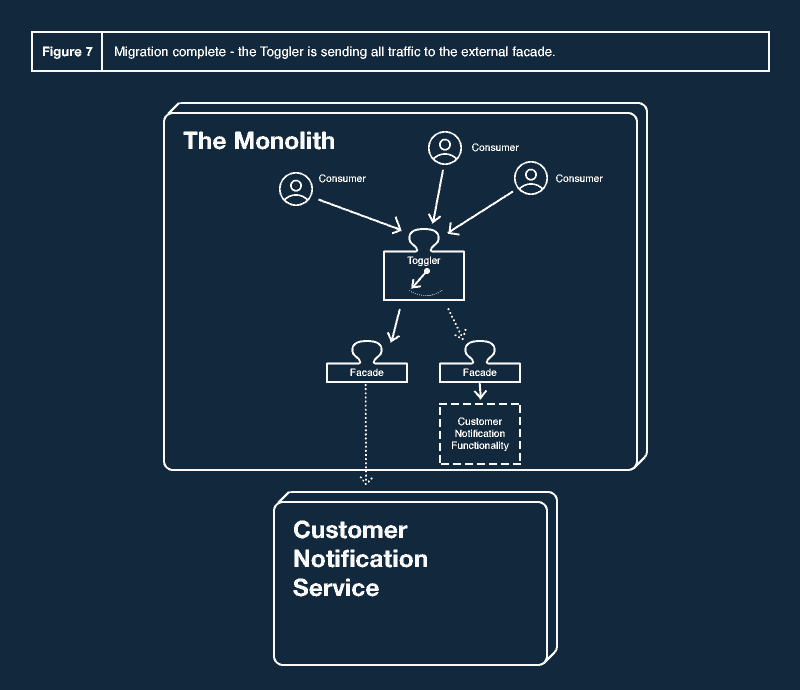

Migrate

We’re now ready to start moving over to the next external implementation. We start off with a Canary Launch, configuring the Toggler’s feature flag such that 2% of requests to the customer notification Toggler is routed to the external facade while the remaining 98% is routed to the existing internal implementation. Assuming things go well we can slowly ramp up traffic to the new implementation until eventually 100% of customer notifications are being delivered via our next external service.

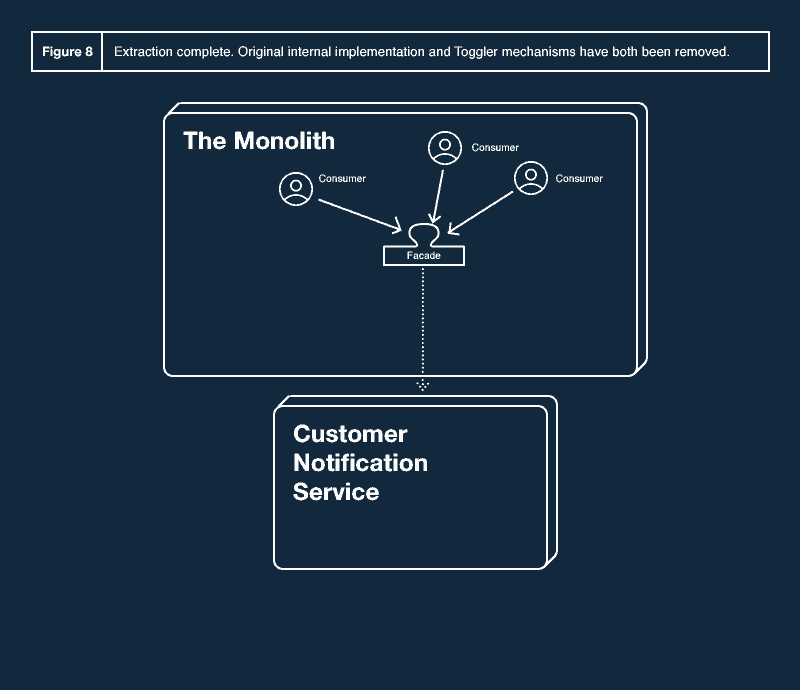

Clean Up

Once we are comfortable that our new external implementation is performing as hoped we get to another fun part — deleting code! At this point, we can remove the now-deprecated internal implementation of the customer notification functionality. We can now also remove the Toggler and hard-wire the consumers of the functionality to the external facade. After those two operations are done we may want to also do some refactoring of the interface exposed by the facade. It’s quite likely that we had to add some non-optimal usage patterns to accommodate our ‘crufty’ legacy implementation. Now that we’re free from that constraint we can take the opportunity to improve the abstraction provided by the facade.

Gotchas

There are two common mistakes that teams make when performing this sort of incremental architectural improvement. The first is to succumb to the fallacies of distributed computing and design the interface of the initial, internal facade as if the facade will always be implemented locally within the same process. Consumers of the functionality behind the facade will eventually be talking to an external implementation, and we cannot abstract that behind the facade. The facade’s interface should reflect the fact that it will eventually be implemented as a distributed system. This means things like not creating synchronous request/reply interactions, and expecting a broad range of failure modes.

The second mistake which I often see is for teams to take this opportunity to “fix” how the functionality has been modeled. Perhaps previously we had email, SMS, and in-app modeled as four distinct interactions but we now realize that they’re really three different variants of the same action. We will be tempted to re-model the notification functionality in this way when we create our new external implementation. The problem with this approach is the new model almost invariably cannot be perfectly mapped back to the existing implementation. This leads to no end of pain when trying to make both the internal and external facades speak the same interface. It’s much better to take this as a two-step process. First, perform an architectural refactoring to extract functionality without changing its externally observable behavior. Once that has been done and your internal implementation has been removed it will be much easier to “upgrade” the new implementation to reflect your newer model of the problem space.

Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

Almost all the concepts and ideas presented here are Branch by Abstraction techniques which have long been championed by folks like Paul Hammant, Jez Humble, Martin Fowler, Chris Stephenson, Steve Smith and many others. What we’ve seen in this blog post is an application of these techniques in the specific context of a monolith breakup, with our branching decisions powered by feature flags.

That Was an Easy One

We’ve seen that it’s possible to perform relatively large-scale architectural work as a series of small, safe steps. Using techniques like feature flagging also allows us to perform this evolution in parallel with other work happening within the same codebase, and while continuing to deploy our codebase to production whenever we’d like.

I did intentionally pick a relatively easy example for this discussion. Our email notification functionality is stateless, so we don’t have to figure out how to move the existing internal state to a new external store, or how to manage state in both places while we are in the middle of the migration phase. We also picked an example where it makes sense to do a simple canary launch to cut over to our new implementation. In other more risky scenarios, we might instead choose a dark deploy, where we send duplicate requests to both our existing internal implementation and our new external implementation and monitor for differences in functionality or performance.

In Part 2 of this series, learn how to extract a service which is backed by persistent state that initially lives in a monolithic shared data store.

Get Split Certified

Split Arcade includes product explainer videos, clickable product tutorials, manipulatable code examples, and interactive challenges.

Switch It On With Split

The Split Feature Data Platform™ gives you the confidence to move fast without breaking things. Set up feature flags and safely deploy to production, controlling who sees which features and when. Connect every flag to contextual data, so you can know if your features are making things better or worse and act without hesitation. Effortlessly conduct feature experiments like A/B tests without slowing down. Whether you’re looking to increase your releases, to decrease your MTTR, or to ignite your dev team without burning them out–Split is both a feature management platform and partnership to revolutionize the way the work gets done. Switch on a free account today, schedule a demo, or contact us for further questions.